Q: Why are Great Lakes water levels so high?

It’s natural for the Great Lakes to rise and fall over time, but the lakes are currently experiencing a period of record high water levels. The Midwest has experienced extreme rain and wet conditions over the past few years. And the pattern has continued, with water levels expected to stay high in the coming months.

According to data from the Army Corps of Engineers and reported by The Detroit News:

- The Great Lakes basin saw its wettest 60-month period in 120 years of record-keeping (ending Aug. 31, 2019).

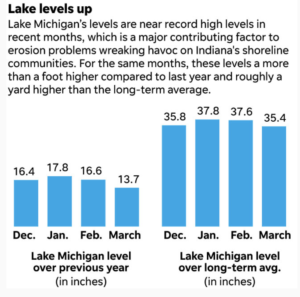

- The Corps’ monthly water levels bulletin showed that the average levels for Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, St. Clair and Ontario in October all were about a foot higher than the same month in 2018.

Q: Weren’t Great Lakes water levels really low not long ago?

Between 1999 and 2014, the Upper Great Lakes (Lake Superior, Michigan and Huron) experienced the longest period of low water in recorded history.

In 2013 the water levels were so low, some residents around Lakes Michigan and Huron even worried that the lakes were “disappearing.” As described in National Geographic, agencies even studied the possibility of building dams or other structures to hold back more water in the lakes.

Within about a decade, the Great Lakes have gone from record low levels to record high levels, a stunningly fast swing. The lakes naturally swing between low and high water levels but typically over several decades. These rapid transitions between extreme high and low water levels now represent a new cycle for the lakes.

Scientists are in agreement that the sharp shifts in water levels are due to climate change. More specifically a warming climate will continue to cause extreme weather, including severe floods and droughts, which spells disaster for lakeside homeowners, towns and cities, tourism, and shipping.

For more, we recommend several helpful articles:

- Drew Gronewold’s (associate professor of environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan) and Richard B. Rood’s (professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan) essay – Climate change is driving rapid shifts between high and low water levels on the Great Lakes – at The Conversation.

- Dan Egan’s (author of The Death and Life of the Great Lakes) 2013 coverage of low water levels from the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel

- Peter Annin’s (author of The Great Lakes Water Wars) 2020 op-ed in the New York Times

Q: What is the impact of currently high Great Lakes water levels?

Even though high lake levels are more apparent in the summer when people are out on the lake, they can actually do more damage in the fall and winter due to intense wind-driven storms that push huge waves up into the shoreline and increase the erosion.

The impact is being felt along lakefronts far and wide. Communities around the lakes are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars, and sometimes millions, to fight the erosion of roads and beaches and to protect national parks. Impacts include beaches that have been swallowed up, bluffs collapsing in western Michigan, stronger currents making swimming more dangerous, and closed water-damaged roads, parks, and bridges.

Our Great Lakes shorelines define our communities and are a vital part of our way of life around the region. While we want to protect our shorelines and our communities, healthy sustainable coasts are tied to our local economies and culture.

But, we can’t resort to knee-jerk, short-term solutions. We have to think – and plan – long-term knowing that the Great Lakes are dynamic systems that will continue to change.

Learn more in this interview with Alliance for the Great Lakes CEO Joel Brammeier on WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Q: Is there anything we can do to prevent damage from high water levels?

In some places, it makes sense to protect breakwalls or other infrastructure already in place. But generally, natural, “living” shorelines are a better long-term choice for the Great Lakes and our communities.

This approach relies on dunes, native plants, natural barrier reefs, and other nature-based solutions. All of these dampen wave action, provide habitat, and create a much needed buffer between the lakes’ damaging waves and homes, roads, and other infrastructure. Check out this helpful video for more information and a look at living shorelines.

In a recent Chicago Sun-Times editorial, Alliance for the Great Lakes CEO Joel Brammeier said: “Infrastructure has been built too close to the shoreline. We are not going back to having an early 19th century shoreline in Illinois, but we need to have solutions where the hardening is less invasive. Planning should mean planning for the next 100 years.”

For more, read an August 2019 editorial from the Chicago Sun-Times and a recent Indianapolis Star article on erosion by London Gibson and Sarah Bowman, or watch this segment from WTTW-TV on high water levels.

Q: Is there anything we can do to lower the level of the lakes?

Any kind of drainage or diversion won’t make much of an impact, and frankly, it’s a bit of a ridiculous idea.

First, it’s just not practical. While the idea sounds easy – just drain the water to somewhere else – it would take a massive engineering feat. You would need to drain about 400 billion gallons from Lake Michigan to lower the water level just one inch.

And second, legally, it’s not an option. The Great Lakes states and provinces spent a decade between 1998-2008 creating a precedent-setting legal standard called the Great Lakes Compact and Agreement. This law bans all significant diversions of water beyond Great Lakes county borders. Any water withdrawal would need to be approved by representatives from all the states in the U.S. and Canada that border the lakes.

It’s important to remember – Great Lakes water levels rise and fall. It’s part of the natural cycle that makes the lakes so special. Over centuries these ever-changing cycles have created some of our most favorite places – Sleeping Bear Dunes, Niagara Falls, Pictured Rocks, Indiana Dunes, and more.

But, climate change is throwing the system out of whack. Scientists believe that water levels are likely to fall again on their own, though no one knows when, and the variable high and low extremes represent the new standard.

For more, take a look at this story on the rising and falling of water levels from WGN.

Q: Will Great Lakes water levels keep rising?

Water levels in the Great Lakes vary naturally over time and will recede eventually.

According to Drew Gronewold, associate professor of environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan, and Richard B. Rood, professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan, “We believe rapid transitions between extreme high and low water levels in the Great Lakes represent the ‘new normal.’”

For more, read this article on the rising and falling of water levels from WGN, and Gronewold and Rood’s essay at The Conversation.

Q: How should property owners along the Great Lakes prepare for both extremes of rising and falling water levels?

In the short-term, building fortifications and walls may seem tempting, but it may not be a good long-term solution due to destruction of native wetlands, species, and habitats. These “solutions” also can cause serious, unintended damage to adjacent properties. Often, they just cause more problems over the long-term than they fix.

Currently, the cities of Quebec and New York’s responses offer a stark contrast. Quebec officials have encouraged flooded property owners to take buyouts to break the cycle of flood-bailout-rebuild, repeat, while New York has encouraged Lake Ontario property owners to armor their shorelines and hunker down.

In the long-term, some towns are establishing regulations to make sure property is built a safe distance away from the shoreline. St. Joseph, MI, established a 200-foot coastal setback to prevent new construction in areas threatened by flooding and erosion.

There’s also a need for more research. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Great Lakes Coastal Resiliency Study (GRCS) would provide the Great Lakes states with region-wide information to help plan for the long-term. Although the study is not currently funded by the federal government, states continue to push for it. Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio and New York have already pledged to help fund the 25 percent non-federal share required to complete the study.

For more, read MLive’s article on the GRCS and Peter Annin’s New York Times op-ed.