For our Diving Deep for Solutions series, we commissioned author and journalist Kari Lydersen to examine big issues facing the lakes today and how our expert team at the Alliance for the Great Lakes is growing to meet the moment.

In 2014, harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie contaminated Toledo’s water system, leaving residents without clean drinking water and leaders scrambling to deal with the public health emergency. It was a symbol of the greatest water pollution threat facing big swathes of the Great Lakes region, even after hundreds of millions of dollars were spent on mitigation efforts sparked by the Lake Erie crisis.

Agriculture is one of the major industries and employers in the Great Lakes basin, producing more than $15 billion in livestock and crops per year. But with current farming methods, the ecosystem can’t handle the massive amounts of runoff from fertilizer – manure and chemical – which pollutes waterways with phosphorus and nitrogen that feed algae blooms. These algal blooms can become toxic – which we have observed in Lake Erie – and can also create “dead zones” by robbing water of oxygen when algae decays.

The problem will only get worse with climate change, which is expected to cause more severe rains and warmer temperatures, meaning more runoff and conditions even more conducive to algal blooms. Meanwhile climate change is also expected to increase the intensity of agriculture in the region, as the growing season gets longer and new crops can be grown further north than before. Pesticide and herbicide use is also expected to increase due to shifting pest pressures linked to climate change. Increased usage of these products may lead to additional surface and groundwater pollution.

Hence, there is no time to waste in addressing the crisis of agricultural pollution in the Great Lakes. The Alliance for the Great Lakes has long been a leader on this issue, including in pushing for the agreement between Michigan, Ohio and Ontario, Canada to reduce phosphorus runoff into Lake Erie by 40% by 2025.

Voluntary measures fail to create significant progress; more aggressive and holistic approach is needed for Lake Erie

It is clear that ambitious target won’t be met, and the Alliance and others are demanding more aggressive policy and a more holistic approach to the crisis.

Tom Zimnicki, Alliance Agriculture and Restoration Policy Director, noted that the agencies involved in the Lake Erie agreement “would be hard-pressed to identify any kind of quantifiable reductions that have been made from agricultural sources” in phosphorus pollution, despite hundreds of millions of dollars spent, mostly to pay farmers to voluntarily implement practices meant to curb runoff, like foregoing tilling, planting grass near waterways, and planting cover crops.

“We haven’t really seen voluntary programs work anywhere,” said Sara Walling, Clean Wisconsin’s Water and Agriculture Program Director, formerly the Alliance’s Senior Policy Manager for Agriculture and Restoration. “That’s not specific to the Great Lakes, it’s a fallacy everywhere. We’re just throwing money at the problem without accountability to make sure practices are implemented correctly, that they actually function as intended to, and are maintained over time.”

The failure to make significant progress through voluntary measures and incentives underscores the need for federal action on agricultural pollution. This includes regulating farm runoff as a point source of pollution – in the same way releases from factories or power plants are regulated.

“Every other industry has standards around pollution prevention and risk mitigation for impacts to human health,” said Zimnicki. “Agriculture shouldn’t be any different. There are nuances to agriculture that make it more complicated than just saying, ‘Here is this manufacturing facility, let’s control what is coming out of that pipe.’ But there are things we can be looking at.”

In 2019, Ohio adopted a program known as “H2Ohio” to reduce nutrient pollution and address other water quality issues. Alliance Vice President of Policy and Strategic Engagement Crystal Davis was part of the technical assistance program for the effort. Davis – who is based in Cleveland – noted that there are multiple measures that could be adopted to quantify phosphorus in waterways, rather than just hoping best practices will reduce pollution.

“There’s edge-of-field monitoring, smart buoys in the water that can tell you how much pollution is in our waterways, we have a myriad of options,” she said.

Following a federal lawsuit, Ohio was required to develop a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for phosphorus – or “a pollution diet” as Zimnicki put it – for the Maumee River, a major tributary of Lake Erie. In September, U.S. EPA approved Ohio’s TMDL, however the plan lacks important conditions needed to improve water quality goals.

Environmental injustice: Downstream water users pay the price for pollution generated upstream

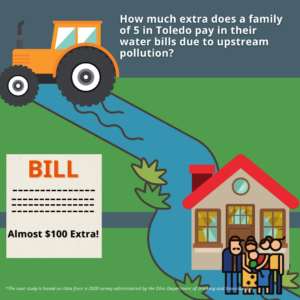

Not only does agricultural pollution pose a major economic and ecological threat to the region, it also can lead to environmental injustices. In the case of the Western Basin of Lake Erie, downstream ratepayers in Toledo bear the brunt of the health and financial impacts of agricultural pollution despite most of that pollution being generated upstream. The financial impacts of pollution exacerbate an ongoing water affordability crisis for lower-income residents of the City.

As the Alliance documented in Ohio, low-income customers struggle to pay a disproportionate amount of their income for water, and are especially burdened when pollution necessitates more infrastructure investments – that are billed to customers, or when they need to buy bottled water because the tap water isn’t safe.

“We don’t have adequate representation from impacted and downstream communities,” noted Davis. “Equitable stakeholder engagement is paramount to the development of a strong plan that holds polluters accountable while making significant progress on phosphorus reduction goals,” Davis said.

A recent study by the Alliance for the Great Lakes and Ohio Environmental Council found that to achieve Lake Erie water quality targets, Michigan would need to increase funding by $40 to $65 million a year and Ohio by $170 to $250 million per year, on top of current spending. Such funding should also be secured long-term, rather than subject to approval in every budget cycle, the report emphasized.

Federal laws offer opportunities to regulate runoff

The Farm Bill and federal pollution laws like the Clean Water Act offer opportunities to regulate agricultural runoff. Some farmers are encouraged to use riskier and more polluting practices since crop insurance covers their losses. Mandates and incentives for runoff reduction could be built into crop insurance, Alliance experts note. Walling said that’s especially appropriate since the government pays for federal crop insurance costs.

“We as the public should be expecting more payback, if you will,” she said. “Not in actual dollars but in more environmental responsibility from the recipients. That’s not happening now.”

The federal government has the biggest role to play in restructuring things like crop insurance, farm subsidies and pollution-related mandates. Especially given the political and economic significance of farming in the Great Lakes states, the states “do need the federal government to come in with a heavier hand and give them a ‘thou shall’ rather than a ‘please,’” said Zimnicki.

The Alliance emphasizes that it is in farmers’ best interest to curb agricultural pollution and protect the Great Lakes, as well as their own bottom lines. And along with mandates, government support is crucial.

“Most farmers do want to leave the land in better shape than the day they took it over,” said Walling. “But there isn’t as much technical support available to help them. Even if something like planting cover crops is shown to benefit their long-term profitability, there’s a cost to making that change: buying that cover crop seed, planting it, changes in their yields as they work out the kinks. Their profit margins are so small, they can’t internalize those costs.”

Farmers and community leaders push change for Green Bay

Green Bay in Wisconsin has also faced severe nutrient pollution from farming and algal blooms that harm the tourism and sport-fishing that is so popular in the region, including Wisconsin’s beloved Door County.

“The entire economy is built around tourism, and access to the lake is the central piece,” said Walling. “Not having solid water quality is going to continue to affect the economic engine.”

In the Fox River basin that feeds Green Bay, many farmers and community leaders have joined the effort to reduce runoff through voluntary measures and educating their peers. Farmers using sustainable practices invite colleagues to tour their farms and learn.

“We’ve seen a lot of good buy-in,” said Walling. “They’re going above and beyond in their conservation, and also being that mouthpiece, inviting other agricultural producers onto their farms, to share information to try to generate more comfort across the agricultural community.”

How to make our region a leader in agricultural practices that protect clean water

Ultimately, farming in the Great Lakes isn’t going anywhere, so the way we farm has to change for the lakes and people to stay healthy. This issue won’t be solved by cracking down on a few bad actors, but by making the Great Lakes a leader in agriculture that actually protects clean water.

As Walling, Zimnicki and other Alliance leaders noted, concrete steps to achieving this goal include:

- Requiring that funding for agricultural best-management practices to reduce phosphorus is tied to reducing phosphorus entering waterways. This means farmers aren’t just paid to adopt certain practices, but instead paid for actually reducing phosphorus runoff.

- Instituting a robust network for water quality monitoring in Lake Erie’s Western Basin.

- Utilizing the Farm Bill to fully fund conservation programs and provide technical assistance for farmers.

- Securing stable streams of state funding for conservation and enforcement and ensuring state-level permits, particularly those for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), provide more rigorous standards for waste management – especially in already impaired watersheds.

These actions and more will be the focus of the Alliance’s federal and state advocacy agendas to reduce agricultural pollution over the next five years.

“The private agriculture sector needs to step up and demonstrate that it is able to operate without polluting our drinking water, just as other industries are required to do,” said Brammeier. “

“Ultimately, companies in the agricultural supply and distribution chain need to acknowledge that clean water is a critical measure of whether they are operating sustainably. The health of the Great Lakes can’t be an afterthought.”